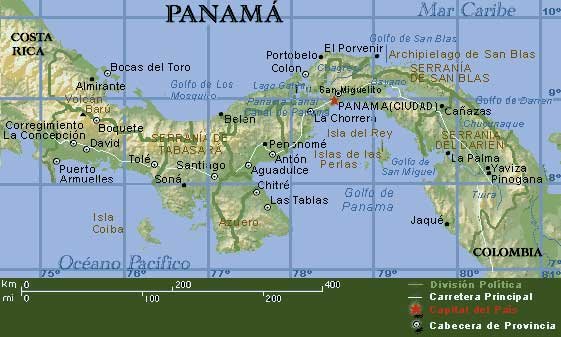

April and Kevin in Kuna Yala, the northeast coast of Panamá

Friday, May 29, 2009

Burning: Why and What are the Alternatives?

Burning: Why and What are the Alternatives?

As summer comes to an end, the pace picks up. Everything is as dry as it will be. Soon, the rains will green everything again, and new trees, brush, vines, and grasses will grow over the trees, brush, vines, and grasses that were cut over the past few months. In other words, better burn the dry stuff now.

Why is slash & burn the preferred method of farm management? What are the gains from this destructive option that outweigh other safer, less-damaging alternatives?

There are several reasons for slashing, and several for burning. The basic slash reason is the paucity of “good” soil here in the tropics. While many of us from the US are accustomed to feet of good, grow-able soil, here in Panama and other tropical lands, the topsoil is often less than a foot, sometimes merely inches. Once exposed from the protection of tree canopy, brush, and detritus, the winds of summer and rains of winter quickly move the soil into streams, rivers, and the ocean. Within a few years, a recently but not maintained cleared plot will not grow crops well. So it is time to move to another patch of “good” soil. (At least here in my island community, that frequently means a plot that was previously cultivated and has been let fallow for a few years, so no more “old growth” is normally lost.) Chop through with a machete, and it is ready for planting (or in the case of tirar-ing maize, plant first by tossing seeds so they reach the soil, then cut everything down so sun and rain reach the seeds). It isn’t hard to slash – a day or two’s work and everything is down.

What is the alternative to slashing? Well, for starters, you could maintain the plot you are currently using. Which means adding abono (fertilizer) organico; preventing erosion through live barriers, abonos verdes, and terracing, and drainage catchment systems; and weeding to prevent overrun of your plot by malaisas. Those efforts, which SAS and CEC learned in Pre-Service Training on a small scale, take time, especially if you are trying to apply them on a large scale. A lot more time and effort than a few days of slashing.

As for burning, once you’ve cosechar’ed (harvested) that primero coa de maize (first planting of corn) in your slashed plot, the time has come to burn down the now dried materials. Burning removes the sticks and stumps from the field, and adds ceniza (ash), with its associated nutrients. This serves at least three purposes: one, it adds (albeit limited relative to alternatives) nutrients and minerals to the soil, which will make your next crop grow better; two, it kills weeds, which decreases the amount of work necessary to maintain the plot; third, it reduces the large debris, so it is easier to move around the plot when planting, weeding, and harvesting. It isn’t hard to burn – a hour or two’s work and everything is aflame.

What is the alternative to burning? Presuming you’ve already slashed, then you could use the same plot without burning (possibly you already did this with that first coa de maize). The downed trees could be placed horizontally as dead barriers for erosion control. You could weed really well right away, while the weed counts are low; and you could plant abonos verdes, such as mani forajero or canavalia to help control weed populations. These efforts take time, a lot more time than a few hours of burning.

Another option is to mulch all the downed material. Smaller items (leaves, twigs) can be piled for compost, but branches, limbs, sticks, and trunks are too large. A chipper shredder would be required. This takes time to transport and time to use (the gallon of gas to run it we’ll call a wash with the gas to start the fire if burning). And you still haven’t really addressed the weed seed issue. A lot more time than a few hours of burning.

So, it sounds like in terms of the farmer’s short term perspective, slash and burn is the easy and positive winning option. Less work, fewer weeds, more nutrients in the soil.

The alternative, for the farmer, requires thinking well into the future, when the effort of maintaining a plot long term begins to pay off through the need for less land, and less distance travelled to that land. If the same plots could be used over and over, all your land can be in use at once; there is no need to allow a plot to revert to monte (transition level growth between grasses and true forest) so it will grow material for later burning for nutrients, etc.

So why are we against burning? Why is burning bad? By whose values? There is an image of burning as a terrible thing – dirty, polluting, resource consuming, illogical. Is that because it is a single big event? Like our fascination with plane crashes even though they are less threatening than car crashes, burning a single big burn is more noted than the small, less visual, impacts of tailpipe emissions, etc. What is dirty and polluting? Burning a hectare of monte releases CO2. Driving a car releases CO2. Which is dirty and polluting? What is resource consuming? While natural resources may be lost, we’ve already seen that more immediate resources (time, money) would be necessary to implement alternatives to burning.

So what can we, as Peace Corps Volunteers, do? We can bemoan the burning. But most folks will still do it. If we feel that it is really important enough, that our values can be understood by our community members, then we must provide alternatives that are feasible and adoptable. Maybe start with your MIDA (Ministry of Agriculture) or ANAM (Environmental Authority) office to talk about a demonstration plot of mulching, with a multi-year use plan. Maybe with a community farmer, so others understand it can be done and isn’t all due to MIDA magic or ANAM abono while they aren’t looking. Or you start with talking to community farmers about why they burn. Ask, don’t lecture. Learn, don’t teach. Start early. After a while, offer alternatives to their reasons for burning. By your second year, maybe you’ll find someone willing to implement some of the ideas. Then call in MIDA or ANAM or other PCVs to help you start, so they see there is interest and they aren’t alone.

By the time you leave, maybe one small plot less will burn. Congratulations. That’s your reward.

Kevin Cropper is a SAS PCV in Group 59. He loves the smell of a campfire, but not a forest fire. He hasn’t figured out how to determine if that one plot less burned, thanks to his efforts.

Sunday, May 24, 2009

Off to Coiba!

I (April) am off to Coiba National Park today to teach a Certified Interpretive Guide course with park rangers there. In this case interpretation means interpretation of a history, resource or other story....such as guided hikes that our National Park Rangers do in the States...they help you interpret what is unique and important about what you are seeing/experiencing. The training will be an official course within the curriculum of National Association of Interpretation. (See their webpage at http://interpnet.com/ to learn more about interpretation as a profession and a skill set.)

As my parents have heard... I originally proposed this week long class last February. I wrote the proposal three times before it was accepted (English, Spanish, and official government format Spanish). The course has been postponed twice...once in November due to a broken electric generator and again last month for unknown reasons (internal agency confusion seems likely on that one :)

The funding has come from the national environmental agency ANAM and all of the students are ANAM employees. All told we hope to have representatives from 7 different Panamanian parks in attendance. I even have a wonderful co-instructor to share the work with...Eylin Martinez is a Panamanian who also holds the certification from the National Association of Interpretation. I am so lucky that she is donating her time and efforts to this workshop...she brings a great point of view, excellent Spanish and a cheery disposition. All in all she is quite likely to be the main reason I survive the week with any sanity. Thank you Eilyn!!!

So, off I go to fix up the last minute details and make the last of the copies needed. I will post later about how the class went...with photos of course. If I get lucky I may even get in some snorkeling time...I am taking my gear just in case.

Saturday, May 23, 2009

Boat Repair

It was still there when we moved in in November 2007. It stayed for December...and January....and on and on. We got used to using it as a type of bench. Then April told the owner that she was going to move it...he just needed to say where to put it.

Then the first weekend of May 2008 (less than 2 weeks after April asking where to put it), we came home to find that the boat was no longer there. Our neighbor had finally moved it into his front yard. It stayed there for about a month, before moving into the Casa Comunal (a very similar design to our house, but much bigger) across the field. Over the course of the last year, they worked on it, practically taking it apart and expanding it into something larger. The finished boat was about 1 1/2 feet wider and a couple of feet longer than the original. They put fiberglass on it, and put it in the water around January of this year.

And the fiberglass separated.

So they pulled it out in the cove near our house, cut off the fiberglass, and put on a new layer (ouch, expensive mistake, since everyone would like to fiberglass their boats to make them last longer and float lighter, thus using less gas, but it isn't cheap).

Then they pushed it back into the water.

After cutting some lengths of a trash tree (grows really fast, dies fairly soon, and isn't good for anything other than making O2) to serve as rollers, they recruited a bunch of neighbors and kids to move it back into the water.

The art of making and using an all wooden boat is not lost in our community, but in our two years here we have seen an acceleration of the change away from natural local materials. We have also seen at least one small boat handmade from a single log...but there are not that many big logs anymore to use this way. Things will always change, the changes just feel faster sometimes when you can actually see them in progress.

Wednesday, May 20, 2009

Money in Panama

But while Panama uses US coins, there are also Panamanian versions of the coins as well, and the peso (50-cent piece) is actually used with some frequency. All the coins have the same composition as their US counterparts. I have not been able to figure out yet where their coins are minted however. And they do not seem to mint every year. I have found quarters, dimes, nickels, and pennies from 1996 (when the shields got smaller and other design changes were made) and 2001 for example, but nothing in between and only quarters since, with 2003, 2005, and 2008 versions, each with a different design. As they are the same size and have the same value as their US versions, you'd have no trouble spending Panamanian coins in the United States.

In recent years, the US Mint has begun a program of changing the obverse or reverse of US coins, making your pocket change much more interesting to look at and much more popular with coin collectors, who now try to hoard a copy of each style. Panama has been making small changes for years. Here are some of the versions I've collected in our time here.

Similar to in the states, one cent is called un centavo. But not a "penny".

The five cent piece in Panama is an integral part of the monetary system. Instead of a "nickel", it is called un real. And many items are commonly priced in reales. For instance, if you buy a soda for 20 cents, the shopkeeper will likely say, "cuatro reales", or "four nickels". This is true at least up to items that cost a dollar. So something that costs 75 cents would be "quince reales" or "fifteen nickels", not "setenta-cinco centavos".

You'll have to refer to the picture above of all the coins to judge the size, but Panamanian ten cent pieces (un decimo de balboa) are the same smallness as US dimes and are probably the most boring of Panamanian coins.

(Panamanian ten cent pieces don't have their own name, like "dime". These two reverses show two shield designs, the newer slightly smaller.)

To me, the 25-cent piece is the most dynamic. Here is the obverse (the Balboa profile) and five of the six reverse designs I have seen (I was missing the Childrens' Hospital, the newest design, that day).

(Panamanian Quarters, with from top left, the original shield design (at least 1966 to 1993), the smaller shield design without bottom fronds (1996 and 2001), the Panama Vieja tower (2003), the Puente del Rey (2005), and the Protégete Mujer (2008) with a Protect Women ribbon.)

Monday, May 18, 2009

Update on Library Progress

Well, it isn't quite like that, but we've certainly seen an uptick in organized scheduling of activities. Last Sunday, we had a community meeting about the library, to discuss where to house it and how to use it. Attendance was limited, but with Cecilia and Maria Luisa (two of our host moms and community leaders) there, it was very productive, and they decided to talk more about it on Wednesday at a Padres de Familia meeting at the school. They assigned each person (well, everyone but us, which was a pleasant surprise) at the Sunday meeting a section of the island to alert about the Wednesday meeting. It was amazing how quickly the word got around; I left site Monday and was asked Monday afternoon about the meeting.

On Wednesday, we had 27 people at the meeting at the school, including the maestra. Cecilia led the discussion and guided them through deciding where to store the books and how to make the books accessible to the community. It was amazing, organized, and productive.

(One of the best parts about this meeting? April and I understood about 97% of the conversation, even when multiple people were talking. What a change from our first Padres meeting we attended!)

The current plan is on 21 May, they'll use a chainsaw to make planks out of a tree that is already down on the school property, which is where they intend to house the library until they can build it its own house off school property. Then on 23 May, they will have a junta (work party) to build bookshelves, which they decided on in the meeting as the best way to make the books visible and upright with spines readable.

On 5 June (April will be gone a week in the midst of that to teach a course at Isla Coiba National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site), they will transport all the books to the school, organize them. And we will discuss amongst the volunteers interested what hours it will be open. (Transporting and organizing the books will be a hefty effort. Between the books we have and the books Cecilia has from a Club de Leones - Lions Club - donation, there are probably 10 or 11 ft of books, around 300, from thin kids books like Dora the Explorer, to the first three Harry Potter's, to thick health books, like Donde No Hay Doctor - Where There is No Doctor - and Qué Se Puede Esperar Cuando Se Está Esperando - What to Expect When You're Expecting.)

Finally, on 9 June (si Dios quiere - God willing), they will have an Opening Party to open the library to the community, announce office hours, and demonstrate the check out procedure, which was the other part of the library discussion at the meeting. After much consideration and discussion on the relative merits of protecting the books by not allowing them to leave the room versus giving people the chance to read at their leisure and to their kids by allowing them to take them home, as well as how to plan for replacements of damaged books, they decided:

- Adults only may check out books;

- Two weeks is the check-out period;

- No deposit is necessary to check out a book;

- One book at a time;

- Privledges will be suspended if you destroy a book;

- Renewals are allowed, but you must bring the book back to request checking it out again

But the other big topic of discussion during the meeting was the interest in making an Estufa Lorena at the school. So, overlapped with that schedule of events for the library, they intend to modify the table in the kitchen, collect materials, and build an Estufa. After two years encouraging the construction of a school estufa, it is thrilling that they are going to do it, but we really wish they would have decided this a few months ago.

So now we're talking about a lot of work in the time remaining. Maybe those experienced volunteers were right. We'll be sure to warn the newbies on what to expect.