(Ed. Note: I originally wrote this a couple of months ago for La Vaina, the PC Panama revista (magazine) that comes out every regional meeting (now every four months). La Vaina has articles from the office about on-going work, as well as summaries of various committees and groups, and photos and stories or other submissions from volunteers, covering everything from what is the best cheese-puff in Panama, to thoughts on sustainable development, to recipes for zapallo soup (zapallo is like pumpkin; remember when we carved some with our neighbors?). In Panama, La Vaina means "the thing", as in "da me la vaina allá" - "give me the thing there". Back issues are available online at the Friends of Peace Corps Panama website. Sorry I didn't get any photos to submit with it, although one of the editors added one of some small burns on a hillside; you can find the article - minus the last two paragraphs - and his photo in the May 2009 issue.)

Burning: Why and What are the Alternatives?

As summer comes to an end, the pace picks up. Everything is as dry as it will be. Soon, the rains will green everything again, and new trees, brush, vines, and grasses will grow over the trees, brush, vines, and grasses that were cut over the past few months. In other words, better burn the dry stuff now.

Why is slash & burn the preferred method of farm management? What are the gains from this destructive option that outweigh other safer, less-damaging alternatives?

There are several reasons for slashing, and several for burning. The basic slash reason is the paucity of “good” soil here in the tropics. While many of us from the US are accustomed to feet of good, grow-able soil, here in Panama and other tropical lands, the topsoil is often less than a foot, sometimes merely inches. Once exposed from the protection of tree canopy, brush, and detritus, the winds of summer and rains of winter quickly move the soil into streams, rivers, and the ocean. Within a few years, a recently but not maintained cleared plot will not grow crops well. So it is time to move to another patch of “good” soil. (At least here in my island community, that frequently means a plot that was previously cultivated and has been let fallow for a few years, so no more “old growth” is normally lost.) Chop through with a machete, and it is ready for planting (or in the case of tirar-ing maize, plant first by tossing seeds so they reach the soil, then cut everything down so sun and rain reach the seeds). It isn’t hard to slash – a day or two’s work and everything is down.

What is the alternative to slashing? Well, for starters, you could maintain the plot you are currently using. Which means adding abono (fertilizer) organico; preventing erosion through live barriers, abonos verdes, and terracing, and drainage catchment systems; and weeding to prevent overrun of your plot by malaisas. Those efforts, which SAS and CEC learned in Pre-Service Training on a small scale, take time, especially if you are trying to apply them on a large scale. A lot more time and effort than a few days of slashing.

As for burning, once you’ve cosechar’ed (harvested) that primero coa de maize (first planting of corn) in your slashed plot, the time has come to burn down the now dried materials. Burning removes the sticks and stumps from the field, and adds ceniza (ash), with its associated nutrients. This serves at least three purposes: one, it adds (albeit limited relative to alternatives) nutrients and minerals to the soil, which will make your next crop grow better; two, it kills weeds, which decreases the amount of work necessary to maintain the plot; third, it reduces the large debris, so it is easier to move around the plot when planting, weeding, and harvesting. It isn’t hard to burn – a hour or two’s work and everything is aflame.

What is the alternative to burning? Presuming you’ve already slashed, then you could use the same plot without burning (possibly you already did this with that first coa de maize). The downed trees could be placed horizontally as dead barriers for erosion control. You could weed really well right away, while the weed counts are low; and you could plant abonos verdes, such as mani forajero or canavalia to help control weed populations. These efforts take time, a lot more time than a few hours of burning.

Another option is to mulch all the downed material. Smaller items (leaves, twigs) can be piled for compost, but branches, limbs, sticks, and trunks are too large. A chipper shredder would be required. This takes time to transport and time to use (the gallon of gas to run it we’ll call a wash with the gas to start the fire if burning). And you still haven’t really addressed the weed seed issue. A lot more time than a few hours of burning.

So, it sounds like in terms of the farmer’s short term perspective, slash and burn is the easy and positive winning option. Less work, fewer weeds, more nutrients in the soil.

The alternative, for the farmer, requires thinking well into the future, when the effort of maintaining a plot long term begins to pay off through the need for less land, and less distance travelled to that land. If the same plots could be used over and over, all your land can be in use at once; there is no need to allow a plot to revert to monte (transition level growth between grasses and true forest) so it will grow material for later burning for nutrients, etc.

So why are we against burning? Why is burning bad? By whose values? There is an image of burning as a terrible thing – dirty, polluting, resource consuming, illogical. Is that because it is a single big event? Like our fascination with plane crashes even though they are less threatening than car crashes, burning a single big burn is more noted than the small, less visual, impacts of tailpipe emissions, etc. What is dirty and polluting? Burning a hectare of monte releases CO2. Driving a car releases CO2. Which is dirty and polluting? What is resource consuming? While natural resources may be lost, we’ve already seen that more immediate resources (time, money) would be necessary to implement alternatives to burning.

So what can we, as Peace Corps Volunteers, do? We can bemoan the burning. But most folks will still do it. If we feel that it is really important enough, that our values can be understood by our community members, then we must provide alternatives that are feasible and adoptable. Maybe start with your MIDA (Ministry of Agriculture) or ANAM (Environmental Authority) office to talk about a demonstration plot of mulching, with a multi-year use plan. Maybe with a community farmer, so others understand it can be done and isn’t all due to MIDA magic or ANAM abono while they aren’t looking. Or you start with talking to community farmers about why they burn. Ask, don’t lecture. Learn, don’t teach. Start early. After a while, offer alternatives to their reasons for burning. By your second year, maybe you’ll find someone willing to implement some of the ideas. Then call in MIDA or ANAM or other PCVs to help you start, so they see there is interest and they aren’t alone.

By the time you leave, maybe one small plot less will burn. Congratulations. That’s your reward.

Kevin Cropper is a SAS PCV in Group 59. He loves the smell of a campfire, but not a forest fire. He hasn’t figured out how to determine if that one plot less burned, thanks to his efforts.

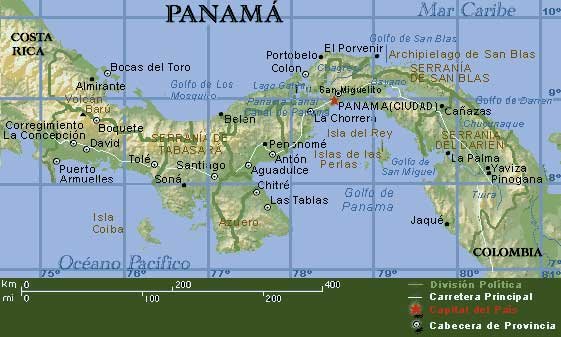

April and Kevin in Kuna Yala, the northeast coast of Panamá

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

What about the risk to life and property if and when the burn gets out of control? Seems like reason enough end the burning. Plus, good hard back breaking work beats the easy (lazy) way every time. The back breaking work helps keep the blood pressure down. The burning only raises the blood pressure worrying about the fire getting out of control.

Post a Comment