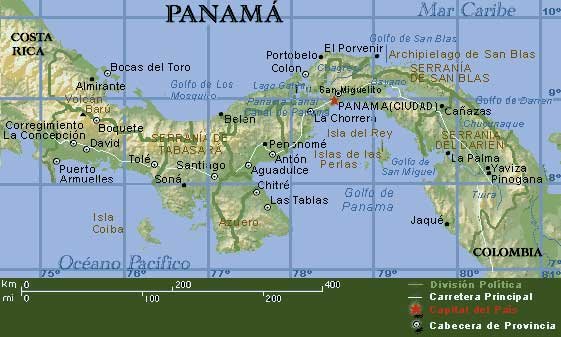

April and Kevin in Kuna Yala, the northeast coast of Panamá

Saturday, March 28, 2009

Minute Man and the Milky Way

So I got the house ready for leaving, putting the parts of the kitchen (which is outside) in the back room, pouring out the pee container, burning the toilet paper, and taking down all but one of the hammocks. I set the alarm for 3:36am, which would give me more than enough time to get dressed, drink a glass of water, grab some bread, tie up the trash bag to carry out, and sit in the hammock to await the sound of a boat (while Efrain may be fairly timely, we've learned to be patient awaiting rides out, especially in the madrugada; the hammocks go away in the morning). And I went to bed.

"¡KEVIN!"

Huh?

"¡KEVIN!, ¿esta listo?"

OH MY GOSH, I must not have heard my watch alarm! Nor my phone alarm?

"Si Efrain. Uno momento."

What time is it? Wait, it is 3:32am! He's early!

So I hopped up, pulled on my clothes, grabbed my bag, stuck the water filter in the back room, and left the trash and the hammock; Efrain was ready to get back in the boat. My watch alarm to wake up went off as we were pulling out of our cove. I felt like a Minute Man.

But a two hour ride to port starting at 3:30am can be beautiful. There are no lights along the Gulf (it is a RAMSAR Treaty Protected Wetlands Area) and the view of the stars can be amazing. Although there was a stretch where I thought at first that it must have been cloudy, since the stars were almost blurry and the background was greyer / less black. But over the course of the entire ride, that section of "clouds" never moved. I realized this was a different, early morning, section of the Milky Way from the more distinct stars-on-a-whiteish-background portion we can see in the evening, when we more commonly are out looking up at the stars. (My reaction reminded me of Barack Obama's similar description of watching what he initially thought were unmoving clouds over stars while in Kenya in Dreams From My Father, which I'd initially scoffed at, "knowing" what the clear whiter stretch of the evening night sky was.)

That amazing section of the Milky Way and the other constellations and the several shooting stars visible in the vast expanse of sky were also reflected on the mirror smooth water ahead of our wake. Despite the early hour, I kept my watch, like a Minute Man soldier of old, on the ever constant yet ever intriguing view of a clear star-filled night sky free of light pollution.

Sunday, March 22, 2009

New Latrine at the School

Thursday, March 19, 2009

Boat Progress - Painting, roof, tools

If you recall the last photo, there were still some boards missing on the sides. Now Pedro has put the sides together, along with most of the top.

Alex (who did go to the demo farm with me) is the one paying for the boat to be made, and he and his family have been a part of the process too.

I can't figure out why they painted the floor, because if he is going to put cattle in it, normally there is a floor of boards over the bottom.

Monday, March 16, 2009

Visit to Demonstration Farm (and the biggest lemon I've ever seen)

I arranged a visit on 20 January to Dario's finca on the mainland so the island cattlemen could see firsthand how he was doing things. They also scored some seeds for the biggest lemon I've ever seen.

It turned out only three of the cattlemen were interested and able to go that day, but that was a good number, as they could see everything easily and ask questions without hiding quietly in a crowd. We started just outside his house, where his wife (who is very involved in the farm; they both made the point that it is a family farm and family effort) explained their data keeping methods and financial recording, and why it is important.

That is not something many small farmers think about, the full cost of items from the start to the end; there are stories of farmers selling their crop or animals and thinking they've made a big profit because it is much more than they paid for the seeds or baby animals, but they have never calculated in the intermediate costs of time, fertilizers or food, pesticides or vaccines, or other supplies, and in reality, they are lost money on the deal. It seems most of the larger cattlemen on the island are making money, but they may not be tracking their costs to know how much.

Then Dario came back and we headed out into the fields to look at the grasses and other plants he grows to feed the cattle, how he has sub-divided his pasture land to rotate the cattle, and the trees and other products he has incorporated into his farm planning.

(Alex, from the island, walking through a plot of buton de oro, which grows about eight feet tall, has pretty flowers, and is an important component of the silage they produce)

(Alex, from the island, walking through a plot of buton de oro, which grows about eight feet tall, has pretty flowers, and is an important component of the silage they produce)We walked past some other examples of sustainable agriculture as well, including several varieties of compost piles.

(Julio, who also owns the upper tienda on the island, feeds sugar cane and buton de oro into the chipper shredder)

Julio currently cuts up sugar cane by hand with a machete to feed his cattle, a process he felt was fairly easy. His mind might have been changed by trying out the chipper/shredder.

By all accounts, it was a worthwhile and enlightening trip for the cattlemen from the island and several of them said they intend to implement some of the process they'd observed. Now I just need to follow up with them occasionally to help it happen and encourage them to share what they learn with others on the island.

By late morning, we returned to port. While grabbing lunch before the return boat ride (yes, out and back in one day; while rare, it is possible, especially if you plan it and go with the capitan, who in this case was Pedro), I watched the TV in the restaurant, which for a while was on a live feed of the Presidential Inauguration from the US; as April said, I cried for the national anthem.

Oh, and if you read through all this just to see a picture of the biggest lemon I've ever seen, here you go:

(Pedro, holding up the lemon from Dario's farm that he is going to bring home and collect seeds from to try to grow his own; he told me later it made good lemonaid)

(Pedro, holding up the lemon from Dario's farm that he is going to bring home and collect seeds from to try to grow his own; he told me later it made good lemonaid)Wednesday, March 11, 2009

Our new Solar Oven

Well, I understand why Bill was hooked. It is a pretty cool stove, and works well with full sun. It is incredibly simple and easy to clean. I was also thrilled that I can use the pots as mixing bowls...something that I was lacking. They also serve well for overnight storage of food.

Why cook solar? The Solar Household Energy (SHE) webpage says:

Currently, more than half of the world’s population relies on biomass (wood, animal dung and crop residue) for cooking, according to the U.N.’s World Health Organization (WHO). This practice causes disease, economic hardship, and environmental degradation. Modern solar cooking ovens like SHE’s “HotPot” offer practical, affordable, long-term relief.

In our community here in Panamá there is evidence of families that suffer from smoke related illnesses. There is a high incidence of respritory illnesses and colds. A couple of the ladies that we work with have even been advised by their doctors that they should avoid cooking with leña (wood) because of the negative impacts of the smoke on their health.

Of course, we were excited to receive it...and so made bread with it the same day. The first 4 photos below are from our first attempt at bread. I made the dough for a white herbed onion and garlic bread. I covered the dough with oil and put it in the pot...

This is what the whole stove looks like, the mirrored surface makes understanding it's shape a bit more difficult.

This is what the whole stove looks like, the mirrored surface makes understanding it's shape a bit more difficult.

Within half an hour of putting it in the sun the glass was steamed up and the pot was really warm to the touch.

The bread turned out really well. It had good flavor and a rich dense even texture. I think that it will work better to let the bread rise more by not pointing it directly into the sun at first. The only problem that I had is that the stove lid catches the evaporation and sends it back into the pot...which is a good thing if cooking soup, a stew, or roasting something, but when cooking bread resulted in a soggy bottom crust.

I also cooked a casserole (rice, mushroom soup, veggies, tuna, and a bit of leftover cheese on top) and that cooked wonderfully in about 3 hours. It was enough food for 2.5 meals for the two of us. Below are before and after cooking photos.

I also cooked a casserole (rice, mushroom soup, veggies, tuna, and a bit of leftover cheese on top) and that cooked wonderfully in about 3 hours. It was enough food for 2.5 meals for the two of us. Below are before and after cooking photos.

Baco's also gave this casserole a good flavor boost.

- rice (too sticky from long slow cooking),

- eggs (hardboiled well without water),

- brownies (my first failure as the sun clouded over about 45 min after putting out the stove...but I cooked them on the stove top as normal and did not mind the excuse to eat a little brownie batter)

- Zucinni / pumpkin bread (done 3 times now and a big hit with everyone who trys it)

- Water (heated to do laundry with hot water...best for the dirtiest clothing)

With direct hot sunlight things cook well, taking about 2 or 3 times as long as normal. This can be an issue if you need to go somewhere or the weather changes. Reheating foods is also possible and doesn't take terribly long. Wind, clouds and curious kids standing between it and the sun can all increase cooking time.

This stove offers a good alternative to fuel based cooking for some types of cooking. It is not a perfect alternative. Solar cooking is more suited to slow cooking foods and can not make fast cooking foods (can't fry with it for example). In our community here in Panama, this might mean that it would receive limited use...maybe for beans and soups and roasts, but it is too cool for frying and cooks rice so slowly that it is more sticky than most would like. It is not reasonable to think that people will change their traditional diet to use a new type of stove, when they still have access to the means to cook traditionally. In areas where the situation is more dire this stove would be more fully utilized out of necessity. Please do not interpret this to mean that my neighbors would not use it, rather it would be one of many cooking methods.

All in all, I am a fan of the solar stove and plan on continuing to try new foods. I particularly want to try to roast a whole chicken without oil or water like the directions book says you can...I think that that might just confirm my "wizard cooking abilities" in the minds of my nieghbors if it goes well. We like it so well that we plan on hauling it (even though it is HEAVY) to the next volunteer conference here in Panamá so other volunteers can see it too.

A big THANKS to Bill and his helpful couriers Linda and Tabassum for this wonderful and very appropriate gift. Our plan is to pass it along to another PVC when we finish here in Panamá so another volunteer (and their curious community) can enjoy it too.

Monday, March 9, 2009

Palm Wine

There are lots of reasons to chop down a tree. Cut it into lumber. Make Firewood. Clear a field. Because it threatened to drop a branch on the house. Because it drops stinky fruit on our porch.

Recently we encountered a new reason: because it makes a vina de palma, or palm wine.

On Ash Wednesday (in other words, the day after four days of Carnaval fun had finished), I was pasear-ing around the island to tell folks about a meeting on Saturday. My last stop was at Ancelmo and Paula's house. They had been our first host family on the island and are always glad to see us. This time, Ancelmo was even more amigable (friendly) than normal; for him Wednesday was the day to finish up anything (alcohol) that hadn't been consumed during the previous four days. After chatting for a bit, they asked if I wanted to see the vina.

Well, I wasn't sure what that was, but I agreed to follow them up into a field. They assured me that it was not that far...and sure enough we soon arrived at where they were making vina de palma and I finally understood. After realizing what it was we were after, and enjoying some good vina (not as much as Ancelmo), I agreed to bring April back the next day. These pictures are from that visit.

The palm (not all types of palms work for this; some are used for their fronds to make roofs, this one is used for wine) is cut down and a hole is cut in the side, near the former top of the tree. There are other countries where palm trees are tapped to make wine rather than cut down, but in the island these trees are basically weeds that are allowed to grow for a few years just so they can be cut to make wine.

The sap continues to climb the tree for about ten days afterward, where it collects enough to empty the hole twice a day. The sap contains natural yeasts that start fermentation immediatly and naturally.

The other option, besides scooping out all the vina into a container to bring back to the house, is to cut a reed that serves as a straw, and enjoy some vina right there in the midst of the long, dangerous thorns that cover the palm.

So how does it taste? If you empty the hole, the next time it will have a very warm initial taste followed by an almost sweet vina. That was how it was the first afternoon I was there. Take a long sip, because while the first taste may be a shock, the rest is better.

But (possibly due to his enjoyment of other beverages earlier that day), they didn't bring the cup to scoop out the hole that first day, this left some of the wine fermenting for another 24 hours. So when we returned with April the next day, the vina had fermented a bit more, and was, as even Ancelmo put it, fuerte (strong).

To keep the sap flowing, after emptying the hole you need to carve off the upper-most layer of the heart of the palm. Like a Christmas tree, this keeps it from sealing over.

Then before you leave, the hole is re-covered with the chunks from cutting it, as well as some of the spikey palm fronds, to protect it from ants, bees, animals, dogs, horses, and neighbors.

The day April and I visited, we didn't partake much of the vina, since it had developed such a strong flavor. But the first day, I'd been hiking and chatting for about four hours by the time I arrived there, and I was thristy. And Ancelmo kept saying, try some more, try some more. The sun was setting, and I needed to walk fast to get back at least to the sidewalk before it got too dark to go safely over the rocky trails.

But the sky and clouds were turning beautiful colors and we were hanging out in the middle of a field drinking from a recently cut palm tree. I just couldn't feel in a hurry to leave. Using a straw, I have no idea how much I sipped, but it wasn't too strong that day, and I made it home happy and safely.

Saturday, March 7, 2009

Estufa Lorena - the first fire

Cecilia and her family did a fabulous job taking care of the stove while it was drying. They did layers of mud and later ash every two or three days as directed on the calendar that we made them to follow. That ability to follow directions is rare in any community, but spectacular here. As a result of their daily work, the stove was beautiful. It looked almost like cement and was wonderfully smooth and dry. Unknown to us, Cecilia had carved our initials into the front of it very prominently to remember us as she uses the stove. Of course, that just upped the ante on hoping the darn thing worked well.

Below is a view of the inside of the firebox (admittedly not the prettiest view) which allows you to see the upward slant of the smoke tunnel as it heads to the second burner. This style of stove uses the hot air for 2 or 3 pots to get the most efficient use of the wood being burned. In the back you can see bits of the original brown clay that she did not cover.

Below is a view of the inside of the firebox (admittedly not the prettiest view) which allows you to see the upward slant of the smoke tunnel as it heads to the second burner. This style of stove uses the hot air for 2 or 3 pots to get the most efficient use of the wood being burned. In the back you can see bits of the original brown clay that she did not cover. Here is the firebox with a fire in it. Getting it to burn well took some practice, Cecilia is used to really packing in the wood (because normally the fire is in an open area) but this smothered the fire a bit in the stove. You can see the pot on the burner, positioned just above the main body of the fire.

Here is the firebox with a fire in it. Getting it to burn well took some practice, Cecilia is used to really packing in the wood (because normally the fire is in an open area) but this smothered the fire a bit in the stove. You can see the pot on the burner, positioned just above the main body of the fire.  Despite good pot placement we had a hard time getting the pot to boil...it formed little bubbles on the bottom but never reached a rolling boil. Not having a rolling boil is a problem, without it no woman would be happy with this stove. We decided that we needed to adjust 3 things:

Despite good pot placement we had a hard time getting the pot to boil...it formed little bubbles on the bottom but never reached a rolling boil. Not having a rolling boil is a problem, without it no woman would be happy with this stove. We decided that we needed to adjust 3 things:- Sand the indents where the pot sits for a better flush seal between pot and stove (and less smoke would escape too).

- Make the burner holes bigger to allow more heat passage to the pot. This limits how small a pot she can use, but made the rolling boil possible.

- Adjust the angle of the roof of the firebox to slope inwards so the smoke would head towards the back and the chimney...not out the mouth of the firebox.

In a true show of self motivation, Cecilia did all of these changes while we were out of town...unheard of! She did a wonderful job...even adding clay to the mouth of the stove in a test to see if that helps to limit the blowback when the wind changes direction. She is an amazing woman. The best part is, after the changes she got the ultimate reward: seeing her changes make her stove work better...she got a rolling boil and cooked her first pot of rice with it.

We were able to use the photo above to illustrate that you can use smaller diameter wood effectively with this stove. The wood on the left is the size she would normally use...a bit bigger than my wrist. The wood on the right is smaller, about the size of my thumb. Both can be used, but normally they would not bother to collect the smaller stuff which is typically blown down rather than cut down.

We were able to use the photo above to illustrate that you can use smaller diameter wood effectively with this stove. The wood on the left is the size she would normally use...a bit bigger than my wrist. The wood on the right is smaller, about the size of my thumb. Both can be used, but normally they would not bother to collect the smaller stuff which is typically blown down rather than cut down.

So what is next? Well, tenemos ganas (we have the desire) to make a stove at the school where the mothers cry from the smoke and sweat from the heat almost every day as they cook lunch. But community development means you do what the community wants to do to better themselves. With that in mind we have a meeting at Cecilia's house on March 5th with the mothers who do the cooking at the shool. The goal is to show them the stove, explain what it is, how we made it, and what are the pros and cons of this type of stove...and then ask if they want one and will work with us to build it with them. I think that they will want one...I mean it is cheap, cooler, safer, no smoke, and less wood to burn. But vamos a ver (we will see) what they want and go from there.

Wednesday, March 4, 2009

Estufa Lorena - mud day

Preparation

The first step was collecting the materials. The ingredients list is pretty simple: barro (soil with a fairly high clay content), arena (sand), estiércol (horse or cow poo), and agua (water). We had actually collected barro and estiercol a while ago with them, and stored it in their chicken coop. The problem came when we did a soil test.

The soil we had collected at Cecilia and Eduardo's didn't show a nice clear thick layer of clay. In a 2 liter bottle test you fill it 1/4 way with soil and hope for 3/4-1 inch of clay. Without enough clay content, the "brick" that becomes the stove wouldn't hold together well. So we had to search for different soil.

We tried a couple other spots near their house, but they didn't have better layers, and Eduardo found a seam of pure clay near the shore, but that wouldn't mix with the other ingredients well, it just formed small balls and rolled off. Finally, we hiked ten minutes up into their pasture and collected small pea sized clay chunks from an ant hill; the ants dig down into the ground to make their home and dump the more clay heavy soil around their hole. The pile was probably two feet tall and three feet around, and was more than enough to augment our existing pile of low-clay soil.

The estiercol was the next problem. It is best collected in dry lumps of cow or horse manure, but it needs to be more of a dust to mix with the other ingredients. So Cecilia and Eduardo ended up putting it in their pilon and pilar-ing it to get it into a dust. (Click here to see a video of pilar-ing rice.)

The arena was simple, since they live on one of the best sandy beaches on the island. The water was not too hard either.

The last prep step was building a base for the stove. Cecilia wanted a cement table, although any really strong table like a packed earth or stone will work too. We measured the height she would want her pots to be at, then subtracted the height of the estufa, and came up with a two-cement-block-high table. Many of the stove tables in our community are too darn tall (some are too tall even for April) because the men build then without considering how tall the cook is.

(Eduardo and Kevin constructing the walls of the table; we left the front open for storage of wood or pots)

(Eduardo and Kevin constructing the walls of the table; we left the front open for storage of wood or pots)Eduardo built the tabletop while we were out of site one time, a pro-active bit of workmanship that was quite pleasant to encounter. So everything was ready and we set a date for the construction. We let other community members know the date, because we figured we would need some help, and we hoped all would go well.

Construction

The morning of construction, we had three youth from the community, including Julito, who had accompanied me to another volunteer's site nearly a year ago to build a couple of estufas, and then Maria Luisa came as well. It was a good thing we had that many helpers, because with collecting an extra sacko of clay from the ant hill, building the formuleta (wooden frame, held together by nails and bailing wire), mixing all the ingredients, and packing them in, it was a long hard day. Luckily, the construction site was under a tree, providing us nice shade. Before rainy season returns, they will reconstruct the roof over the stove.

(The first load of the mix is dumped into the formuleta and packing begins; Eduardo, Maria Luisa, Cecilia, and April ensure the corners are well packed too)

(The first load of the mix is dumped into the formuleta and packing begins; Eduardo, Maria Luisa, Cecilia, and April ensure the corners are well packed too)The formuleta was made from lumber cut on the island. The pieces we'd purchased originally turned out to be an inch or so too short, so we had to cobble together an extra piece to make it tall enough. It didn't impact the end result, but it did delay the start as we cut extra pieces of wood.

Normally the soil mixture is made in parts, instead of all at once because that would be just too much volume to mix with a shovel. The ratio of ingredients is important, as it needs to be damp but not wet, clumpy but not sticky, etc. Each batch is tested with a ball test...a ball the size of a baseball is made and then dropped from shoulder height. In a good mix the ball will land and flatten out to about 1/2 round and show no big cracks. If the test doesn't go well you adjust the mixture until it tests well.

Once it is dumped into the formaleta, it is packed, using a big packer in the middle and smaller ones around the edge to ensure that all parts are well compacted. It is added and packed layer by layer to ensure that it is well packed.

When the formuleta was finally filled, the last touches of packing took place.

Once the formulate was packed full, it was time for lunch, and then we began to remove the wooden frame.

The idea is to be able to use the same formuleta on multiple stoves. We'll have to see if our wood is still in good enough shape to use it again.

Once the formuleta is totally removed, it is time to carve out the firebox, the "burners", the chimney hole, and the tunnels connecting them.

(Cecilia, as the ama de casa, or woman of the house, ceremonially began the carving, cutting out the mud for the mouth of the firebox)

(Cecilia, as the ama de casa, or woman of the house, ceremonially began the carving, cutting out the mud for the mouth of the firebox) It helps to have a child assist at this point, since their small hands work better than big ones in carving the small tunnels with limited access. There should be twenty centimeters between the front of the stove and the first burner, and ten centimeters between all the other holes (in this case, two burners and a chimney) and the edges.

(Cecilia working on the mouth of the firebox, and her daughters Rosaria and Soray carving out the big and small burners respectively)

While the holes are mostly carved with spoons, we also trim off the edges with a machete to remove any sharp edges, both for a smoother result and to diminish the risk of uneven drying and thus cracking. You finish off by using water to smooth out the whole surface and make it pretty.

Then, you have to wait for about thirty days for the mixture to slowly dry. Early on, each day you should apply a watery clay mixture to ensure even drying; later, it becomes an ash mixture instead, to seal it.

(April with her hand in the main burner - the firebox is hidden in the darkness of the front side - a few days after construction)

(April with her hand in the main burner - the firebox is hidden in the darkness of the front side - a few days after construction)Monday, March 2, 2009

Paul and Sandy's Visitor View

“Short” Recap

Panama was about what we expected. Panama is a large metropolitan city surrounded by neighborhoods of varying levels of socioeconomic conditions. We were slightly surprised (but probably should not have been) how poorly many Panamanians live.

The most striking thing for me that was different than I expected was how many Panamanians have cell phones. Regardless of living conditions, they often having more than one phone, and they use them regularly.

About the weather - Absolutely terrific the entire time. Even though it was the dry season and has little rain, we had a 5 day stretch where it rained each day, but not enough to change or alter any of our plans. Temps hovered around 90 during the day with a breeze and maybe high 70s in the evening for lows.

1. A few days in Santa Fe, Veraguas, an hour and a half north of Santiago

2. Several days on their island

3. Four days in Panama City

In Panama City, the bus system around town consists primarily of the famous Diablos Rojos (Red Devils) which are retired American school buses painted and decorated. The drivers of these buses compete for passengers and often race each other to bus stops, since the more passengers they carry, they more they make. Diablos Rojos are considered dangerous, and the government appears to be taking steps to bring these buses under government control, replacing the privately owned Diablo Rojos buses with a conventional public metropolitan bus system.

Santa Fe. The first few days were spent in the mountainous area of Santa Fe. The tallest mountains in Panama are only about 3,000 feet high [Editor's correction: The highest point in the country is the Volcán Barú (formerly known as the Volcán de Chiriquí), which rises to 3475 meters / 11401 ft. but we did not go out that far West. Where we were in Santa Fe is at 400m / 1312ft. above sea level.], so the weather change between Santa Fe and Panama City or even Abril y Kevin's island wasn’t all that dramatic. Maybe just a few degrees or so cooler in general.

1. No endangered species, and

2. No food with hair still on it;

April either ordering or saying “There is still hair there.”

April either ordering or saying “There is still hair there.”

The Island. After Santa Fe we made our way to Abril y Kevin's island via a night’s stay in Santiago to stock up for groceries. We left early the following morning to a cute little port town an hour south of Santiago where April and Kevin depart for their island. Upon arriving, April found we had a couple of choices for rides. April, Sandy & I hitched a ride with Búho (Booho) in a nice fast fiberglass boat. Kevin went with Carlos and family in their slower wooden, leaky boat, only because we had our “cargo” loaded into Carlos’ boat already. We waved at Kevin as we passed them on the way to the island.

Panama City. We spent three full days in Panama City, not counting the travel day to get there and the day we left. It was action packed. Friday we spent at Barro Colorado Island, the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in the middle of Lake Gatun, in the northern half of the Panama Canal. It was a nice visit, yet I came away a bit disappointed, and can’t quite put my finger on why. We saw plenty of animals and plants, and the hike was nice. April felt it too and we think maybe it was because we didn’t hear much about what projects are currently going on and what the various scientists are finding out. Nevertheless, it in general was a fun day.

In first lock of Miroflores locks

A bright yellow building in Casco Antiguo

A bright yellow building in Casco Antiguo

A Cathedral in Casco Antiguo