Hey all,

I have had a lot to say lately... but not the access to the web to be able to say it (unlike Kev:) The following is an excerpt from a letter I wrote home but thought that you all might enjoy it. Thanks to Kristin for sharing her letter...not like she really had a choice. ;) So here is the letter:

"Didn´t know until just now that this white paper looks like a yellow legal pad in candle light. I highly encourage you to light a candle and read the rest of this by candlelight just to be able to enjoy the color change. I thought I had grabbed the yellow pad (I have a yellow one too) but it is the white one. Go on, get out your candles and check it out. I will wait while you get one.

Still waiting..... waiting..... hello there Necio (a puppy at our site)

Got one? Good! Ok, so now that we are both in beautiful candle light, I feel like I should write something worthy of candlelight. Thinking.... should have been thinking while you went for the candle. Thinking... the stars are beautiful here. The Milky Way is quite clear - in it´s ¨milky¨ way. Clear nights are rare - well, clear moments happen often, but that doesn´t mean that they coincide with when I am outside because the weather travels and changes fast. What is clear now might be cloudy in less than an hour - or the other way around. Kevin and I have both noticed that the moon seems very bright here - a clear night with a full moon casts clear bright moon shadows. .

I don´t think I have told you about the fireflys here, but I lose track about what I put into letters and to whom and what went into my journal, so if I did tell you about fireflys you can skip the next part.

Staying with me? Ok, so I was very excited to find that there are fireflys here just like home. Somehow it was calming familiar - just good. I was even more thrilled to find that there are 2 types of fireflys here. The normal one that you know from home and a bigger one. The other one is more orange in color (vs the yellow green of ours at home) and it flashes faster - tends to fly higher and faster and seems larger. Best I can tell, it is a light about the size of my fingernail - but I don´t ever get to see it up close because it flies high and fast and I am slow and not as good as it in the dark. Some day I will catch one. The first time I saw it I was shocked - sooo cool to see a big ass firefly / lightning bug.

Also in the realm of cool night sites - when riding in a boat at night some times there is fosphorescence (or however you spell it - I swear my english is going downhill). Anywho, there is sometimes phosforecence in the water, at times just little glints in the water curling back from the bow of the boat, and you wonder if you are imagining it or if it is really glints of moonlight reflected for a moment by the water. But there are also moments when the entire curl of water streaming away from the bow of the boat lights up like a line of flame from a gas stove only more torquise than blue and a part of your heart gasps at the sight as your mind rushes to believe and record it - you want it to go on and on - but jus as quick as thought it is gone and you are filled with doubt that it was ever really there.

As if that wasn´t enough the water is glossy smooth all around you, the land in the distance on every side looks like a cutout stage prop - too perfect to be real and the ever present Panamanian Thunderstorm is looming over land on one side adding its own light show to the beauty - yellow pink in color and far enough away to not feel worried about getting wet - just yet anyway. Soon dawn will start adding its own touches of beauty to the scene as you watch - fighting a sleepy feeling in the cool but balmy air.

On that note, I will let darkness take this lettre for the night and wish you sweet dreams.

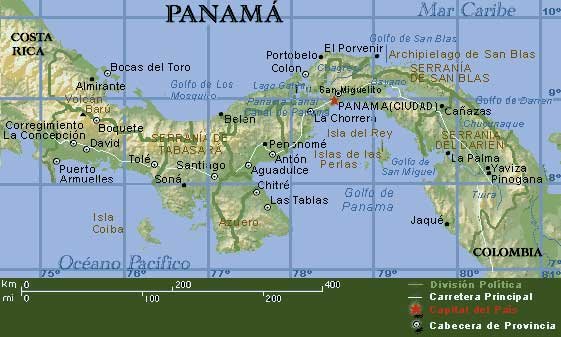

April and Kevin in Kuna Yala, the northeast coast of Panamá

Friday, October 26, 2007

Tuesday, October 9, 2007

Packages and Mail - A short update

Some of you may have noticed an empty post from April titled ¨We have a winner¨ from our last time out. She tried to remove it, because we weren't sure it was ready, but I guess there were Blogspot difficulties. The original intent was to mention that we've heard from two people that they sent packages (one as long ago as during training, about three or four months) that we haven't received yet. But we talked to the Post Office here and they said it could take up to six months sometimes, so we decided to give them some more time.

However, we wanted to update / provide some guidance on what we've learned from the packages we have received. Now that we are collecting our mail directly at the general delivery at the Santiago post office (before, Peace Corps was picking up our mail at one of the Post Offices in Panama City), it seems that letters and packages arrive here within about 10 days to maybe two weeks. Which seems quite rapid.

Picking up letters is easy - they have a stack for people whose last name starts with ´C´ and flip through them. Picking up packages is similar; they log the packages and put a ticket in a book for the ´C´s. Generally, if it is a small package, or a padded envelopes, they hand it directly to us, because we are Cuerpo de Paz, and don't have to pay tariffs, taxes, customs, etc. But sometimes, and it seems more likely when it is a box, they send us next door to the Customs folks. The post office people bring the package to the customs folks, who then hand it to us.

Of course, I'm extrapolating from limited data here, and it maybe in the future that we'll have to open packages for them or something. It may depend on who is working that day, or how busy they are. They seem to know several of the PCVs in our region, at least ones who get a lot of packages I guess.

So, how much does it cost to send a package, what might we want, what can we get here, and such? It seems that most of the packages have been in the $30-$40 range to send, now that the USPS has stopped offering a Book Rate. Which means most things aren't worth sending anymore, especially if they are heavy. Plus, we can find most things we need here: the supermarkets have peanut butter, Gatorade, chocolate, and if we want to pay nearly $4, Nature Valley granola bars (which means that with shipping costs, it would be about the same from the states :)

So what would we like to receive? I wouldn't mind pictures of the seasons, which I'm hoping would make it easier to explain fall (with leaves changing colors) and winter (no leaves, snow, ice). It is hard to describe to folks who have no context for such ideas. If your house has open block windows, with no screens or glass, the concept of what is cold is just very different.

Beyond that, the occasional letter, or an old copy of a magazine, would be great. Oh, and if you try on a pair of shoes, send us the desiccant pack ("Warning: Silica Gel. Do Not Eat!"); we tuck them in with electronics and other stuff we don't want mold growing in. Thanks!

However, we wanted to update / provide some guidance on what we've learned from the packages we have received. Now that we are collecting our mail directly at the general delivery at the Santiago post office (before, Peace Corps was picking up our mail at one of the Post Offices in Panama City), it seems that letters and packages arrive here within about 10 days to maybe two weeks. Which seems quite rapid.

Picking up letters is easy - they have a stack for people whose last name starts with ´C´ and flip through them. Picking up packages is similar; they log the packages and put a ticket in a book for the ´C´s. Generally, if it is a small package, or a padded envelopes, they hand it directly to us, because we are Cuerpo de Paz, and don't have to pay tariffs, taxes, customs, etc. But sometimes, and it seems more likely when it is a box, they send us next door to the Customs folks. The post office people bring the package to the customs folks, who then hand it to us.

Of course, I'm extrapolating from limited data here, and it maybe in the future that we'll have to open packages for them or something. It may depend on who is working that day, or how busy they are. They seem to know several of the PCVs in our region, at least ones who get a lot of packages I guess.

So, how much does it cost to send a package, what might we want, what can we get here, and such? It seems that most of the packages have been in the $30-$40 range to send, now that the USPS has stopped offering a Book Rate. Which means most things aren't worth sending anymore, especially if they are heavy. Plus, we can find most things we need here: the supermarkets have peanut butter, Gatorade, chocolate, and if we want to pay nearly $4, Nature Valley granola bars (which means that with shipping costs, it would be about the same from the states :)

So what would we like to receive? I wouldn't mind pictures of the seasons, which I'm hoping would make it easier to explain fall (with leaves changing colors) and winter (no leaves, snow, ice). It is hard to describe to folks who have no context for such ideas. If your house has open block windows, with no screens or glass, the concept of what is cold is just very different.

Beyond that, the occasional letter, or an old copy of a magazine, would be great. Oh, and if you try on a pair of shoes, send us the desiccant pack ("Warning: Silica Gel. Do Not Eat!"); we tuck them in with electronics and other stuff we don't want mold growing in. Thanks!

Monday, October 1, 2007

A Walk I´d Never Take in Maryland or Virginia

We knew for a while that we had to come to the city this Sunday because we had an informe due Monday and a meeting on Tuesday. And we had asked around for a boat going out and had secured a ride with the dad from our first host house, currently our nearest neighbor, who was leaving at 4am to pick up a political party official for an event that day. Then on Saturday, as we were packing, it turned out the official didn’t want to come because he thought the higher-than-normal tide caused by the full moon would be dangerous (it isn’t), so our ride vanished. Though our experience is limited thus far, it seems like transportation difficulties will be a recurrent theme to our time on the island.

But luckily, my guia, Efrain, came over to visit shortly afterward and said his brother was going off island at 4am too, but leaving from where they live, about an hour’s walk away through cow pastures and muddy trails. So we finished packing, finished transplanting some habichuela (green beans or string beans) into the small garden we’d spent a hot day building for our current host family, and hiked over to the northwest side of the island, luckily without any rain hitting us.

And as we were walking the muddy paths in Tevas and Chacos through waist-high grass carrying a backpack (full of clothes, our laptop, and some books) and our salvavidas (life jackets, or literally, life savers, which Peace Corps requires us to wear while riding in a boat), we both realized that we would never make such a hike so freely in Maryland or Virginia.

For all the worries about deadly bugs and poisonous plants and such here in Panamá, frankly, I was much less concerned here than I would be in a meadow along the AT. Here, there is no poison ivy. Here, there are no Lyme-disease carrying ticks, and there are significantly fewer ticks in general. Here, there are fewer thorny plants, and those few are obvious and avoidable. Here, the ants are only a problem if you stop and stand on them. So the long grass brushing past my bare legs didn’t scare me. (Yes, I do think about venomous snakes, but they behave the same here as rattlers, copperheads, and cottonmouths back home, so I feel the level of danger while walking through the grass is no higher here than in the States.)

Which is good, because I have a feeling we’ll be making such hikes frequently over the next two years. Who knows if it will build up my nerves enough to hike so freely in Maryland. :)

But luckily, my guia, Efrain, came over to visit shortly afterward and said his brother was going off island at 4am too, but leaving from where they live, about an hour’s walk away through cow pastures and muddy trails. So we finished packing, finished transplanting some habichuela (green beans or string beans) into the small garden we’d spent a hot day building for our current host family, and hiked over to the northwest side of the island, luckily without any rain hitting us.

And as we were walking the muddy paths in Tevas and Chacos through waist-high grass carrying a backpack (full of clothes, our laptop, and some books) and our salvavidas (life jackets, or literally, life savers, which Peace Corps requires us to wear while riding in a boat), we both realized that we would never make such a hike so freely in Maryland or Virginia.

For all the worries about deadly bugs and poisonous plants and such here in Panamá, frankly, I was much less concerned here than I would be in a meadow along the AT. Here, there is no poison ivy. Here, there are no Lyme-disease carrying ticks, and there are significantly fewer ticks in general. Here, there are fewer thorny plants, and those few are obvious and avoidable. Here, the ants are only a problem if you stop and stand on them. So the long grass brushing past my bare legs didn’t scare me. (Yes, I do think about venomous snakes, but they behave the same here as rattlers, copperheads, and cottonmouths back home, so I feel the level of danger while walking through the grass is no higher here than in the States.)

Which is good, because I have a feeling we’ll be making such hikes frequently over the next two years. Who knows if it will build up my nerves enough to hike so freely in Maryland. :)

Labels:

First Volunteer Year,

Island life

The Crocodile Hunter

The last time we tried to return to the island, we spent the day in the port unsuccessfully looking for a ride and passed the time chatting with the marine police, store owners, and other regulars who seem to always be there. April also talked to some small tourist boats when they returned from a visit to Coiba. They had a 115hp engine and apparently pass our island in about 20 minutes, as opposed to the two hours it takes us with a 15hp motor. Speed wise, that’s the equivalent of 60mph versus 10mph, and made us kind of jealous (but also happy to know the trip can be made that quickly in an emergency).

We never did find a ride that Sunday, but luckily, my guia, Efrain, happened to come in from the island that morning, and we had talked with him about looking for a ride. We agreed that if we couldn’t find a ride, we’d spend the night with him and his wife in their off-island house, and ride back with them in the morning.

While staying at their house, in addition to talking about the education system here in Panamá with his teacher sister (the entire street is one relative or another), we watched The Crocodile Hunter, dubbed into Spanish, in which they were tagging 17ft crocs and tracking them in northeast Australia. And of course we talked a bit about the fact that there supposedly are American crocodiles (smaller than Australians) in our gulf, although we haven’t seen one swimming or sunning yet (but we’ve seen lots of mangroves, so they could be hiding).

So imagine the irony and our surprise the following morning, just half an hour out of the port, when we spotted the white belly of a five or six foot croc floating in the river. While we still haven’t seen a live one, we can no longer tell ourselves that Panamá’s crocodile population is only in other parts of the country.

We never did find a ride that Sunday, but luckily, my guia, Efrain, happened to come in from the island that morning, and we had talked with him about looking for a ride. We agreed that if we couldn’t find a ride, we’d spend the night with him and his wife in their off-island house, and ride back with them in the morning.

While staying at their house, in addition to talking about the education system here in Panamá with his teacher sister (the entire street is one relative or another), we watched The Crocodile Hunter, dubbed into Spanish, in which they were tagging 17ft crocs and tracking them in northeast Australia. And of course we talked a bit about the fact that there supposedly are American crocodiles (smaller than Australians) in our gulf, although we haven’t seen one swimming or sunning yet (but we’ve seen lots of mangroves, so they could be hiding).

So imagine the irony and our surprise the following morning, just half an hour out of the port, when we spotted the white belly of a five or six foot croc floating in the river. While we still haven’t seen a live one, we can no longer tell ourselves that Panamá’s crocodile population is only in other parts of the country.

Labels:

First Volunteer Year,

Island life

Light, Night, and Waking

Generally we’ve been going to bed between 8 and 9 while in site. The sun goes down around 6:30 and by 7, it is dark. Only one of our three host houses have had working lights, with the batteries in the two others no longer holding a charge from the solar panels. The batteries, good for about five years, cost about $120. One of the two families ironically connected a replacement the day we moved, after we had pointed out that $2 a month for a battery was significantly cheaper than the $15 a month they were paying for gas to run a generator, and the noisy, stinky, generator powered only one light, versus the three fluorescents connected to the battery.

So in the evenings, we generally sit around with a candle, flashlights, or our solar-lid water bottle. Since they all have solar panels on their houses, the only impressive part of that is the size, and its water bottle aspect. But they are so impressed with our Brookstone crank flashlight – thanks M&D Dierks for the birthday present – not needing batteries that one family bought a small hand-squeeze LED light; here’s hoping it lasts long enough to provide a savings over buying batteries every few weeks. We play cards, or talk, and turn in early by US standards (our excuse: our brains are tired from thinking Spanish all day).

We sleep under our mosquito nets (watch for a post later about their benefits besides just keeping away mosquitoes), thankfully sharing a bed again (our second house had us in separate twins). Beds are generally wooden platforms with a foam pad, which we augment with our backpacking sleeping pads, and we bought two nice sets of full sheets. Some nights we’re warm, but some nights after an evening rain can be cooler and we sleep with a long-sleeve shirt for just a bit more warmth. And let’s not talk about Panamanian pillows.

The morning starts around 4am with a flapping of wings (about 5 or 6 times) as the first gallo (rooster) revs up for his call. I can generally turn over for more (fitful) sleep, but it isn’t long before the family gets moving and while quiet, the morning fills with the sounds of hand grinding corn for the tortilla (not like a chip, but a dense, Frisbee-shaped bread, about an inch thick and a foot wide, with a wedge broken off for each person’s breakfast), filing and sharpening a machete, chickens clucking for breakfast, more rooster calls (not just at sunrise, but anytime of day), and the one that prompted me to want to write this post, the pigeon races across the zinc roof at our current house. (Man, are they loud and I think they literally just go back and forth for a while, maybe until they see all the residents emerge from the house.) The smell of coffee mixes with the cooking tortilla, and by just after 6, we’ve gotten up too.

Often (like while I was hand writing this to later type for a blog entry), we sit on the porch enjoying the early morning light and slight cool (and it had better be cool, because we are wearing long pants, long sleeves, and socks to keep off the chitra, which are like the insects in the US known as no-see-ums) while reading or writing. Around 7 we eat, and by 7:30 the day’s work begins (for us, and resumes for them). Once we are out on our own, it will be interesting to see how our schedule adjusts.

So in the evenings, we generally sit around with a candle, flashlights, or our solar-lid water bottle. Since they all have solar panels on their houses, the only impressive part of that is the size, and its water bottle aspect. But they are so impressed with our Brookstone crank flashlight – thanks M&D Dierks for the birthday present – not needing batteries that one family bought a small hand-squeeze LED light; here’s hoping it lasts long enough to provide a savings over buying batteries every few weeks. We play cards, or talk, and turn in early by US standards (our excuse: our brains are tired from thinking Spanish all day).

We sleep under our mosquito nets (watch for a post later about their benefits besides just keeping away mosquitoes), thankfully sharing a bed again (our second house had us in separate twins). Beds are generally wooden platforms with a foam pad, which we augment with our backpacking sleeping pads, and we bought two nice sets of full sheets. Some nights we’re warm, but some nights after an evening rain can be cooler and we sleep with a long-sleeve shirt for just a bit more warmth. And let’s not talk about Panamanian pillows.

The morning starts around 4am with a flapping of wings (about 5 or 6 times) as the first gallo (rooster) revs up for his call. I can generally turn over for more (fitful) sleep, but it isn’t long before the family gets moving and while quiet, the morning fills with the sounds of hand grinding corn for the tortilla (not like a chip, but a dense, Frisbee-shaped bread, about an inch thick and a foot wide, with a wedge broken off for each person’s breakfast), filing and sharpening a machete, chickens clucking for breakfast, more rooster calls (not just at sunrise, but anytime of day), and the one that prompted me to want to write this post, the pigeon races across the zinc roof at our current house. (Man, are they loud and I think they literally just go back and forth for a while, maybe until they see all the residents emerge from the house.) The smell of coffee mixes with the cooking tortilla, and by just after 6, we’ve gotten up too.

Often (like while I was hand writing this to later type for a blog entry), we sit on the porch enjoying the early morning light and slight cool (and it had better be cool, because we are wearing long pants, long sleeves, and socks to keep off the chitra, which are like the insects in the US known as no-see-ums) while reading or writing. Around 7 we eat, and by 7:30 the day’s work begins (for us, and resumes for them). Once we are out on our own, it will be interesting to see how our schedule adjusts.

Labels:

First Volunteer Year,

Island life

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)