Bill Andrews posted a comment asking how folks cook on the island, and we couldn’t have paid him for such a great leading question, as this is one of our first projects we are working on as part of our Peace Corps service! (BTW Bill, please send us more info on your solar stove; we´d be interested in trying one here.)

In Panamá, while most families have a 25-lb. propane tank and a gas stove, the traditional cooking method is a fogon (FUH-goun, rhymes with scone), which is really just three rocks (soccer ball sized) with the fire in their midst.

In Panamá, while most families have a 25-lb. propane tank and a gas stove, the traditional cooking method is a fogon (FUH-goun, rhymes with scone), which is really just three rocks (soccer ball sized) with the fire in their midst.

(Here is April proudly showing off brownies she cooked on a fogon using an ingenious nested pot system to serve as an oven. Wow that was yummy!)

Ollas (pots) of many sizes can be balanced on the stones for cooking; rice, soups, beans and lentils, boiling corn, and other long-cooking items are all cooked this way to save gas. (Frying plantanos, fish, or eggs and other foods that don’t need to cook as long, is done on the gas stove, although I haven’t really discerned a real plan for how long things cook; I’ve seen spaghetti noodles at a rapid boil for over 20 minutes, and a big pot of rice reheated for just a minute. I think things cook until you remember them sometimes.)

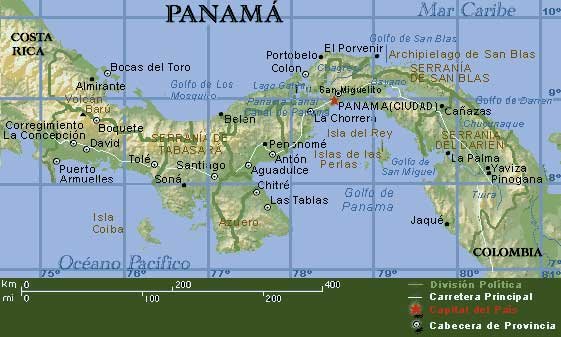

Ironically, this combination of cooking methods was just as true in our training community, about an hour outside Panamá City, as it is here in the island. Our host mom there had a fogon out in a gazebo type structure there as well, and actually used it almost daily. But here on the island, most folks have the fogon much closer to their kitchen.

And this brings us to why April and I are working on the cooking methods. As you can imagine, the fogon design is not overly efficient and can be rather smoky. Sometimes the kitchen, sometimes the entire house, will be filled with smoke, and often our clothes, hanging on the line near the fogon area, would come down clean but smelling of smoke (sometimes better than the slightly moldy smell they’d take on after three grey, damp, days on the line ;). The mother of the house, who will often spend a large portion of her day either cooking on the fogon, tending the fogon, or working near the fogon, will breathe in a lot of smoke while tending an open fire. Some older women have been told by doctors that when they start coughing a lot, they shouldn’t use the fogon for several days. In addition, firewood must be collected and split almost daily, and even on an island as large as ours, there is a limit to how much wood you can cut.

Which brings us to the estufa lorena, which I think originated in Africa. (Here is a picture of April working on a split-open model of an estufa for a talk we gave on its designs and benefits.)

Ironically, this combination of cooking methods was just as true in our training community, about an hour outside Panamá City, as it is here in the island. Our host mom there had a fogon out in a gazebo type structure there as well, and actually used it almost daily. But here on the island, most folks have the fogon much closer to their kitchen.

And this brings us to why April and I are working on the cooking methods. As you can imagine, the fogon design is not overly efficient and can be rather smoky. Sometimes the kitchen, sometimes the entire house, will be filled with smoke, and often our clothes, hanging on the line near the fogon area, would come down clean but smelling of smoke (sometimes better than the slightly moldy smell they’d take on after three grey, damp, days on the line ;). The mother of the house, who will often spend a large portion of her day either cooking on the fogon, tending the fogon, or working near the fogon, will breathe in a lot of smoke while tending an open fire. Some older women have been told by doctors that when they start coughing a lot, they shouldn’t use the fogon for several days. In addition, firewood must be collected and split almost daily, and even on an island as large as ours, there is a limit to how much wood you can cut.

Which brings us to the estufa lorena, which I think originated in Africa. (Here is a picture of April working on a split-open model of an estufa for a talk we gave on its designs and benefits.)

Constructed of clay, sand, and grasses, it functions a bit like a masonry heater or a brick oven. With only one opening in the front for tending the fire (compared with the easy 360° access of a fogon), it contains the heat much better. With two openings on the top, it can cook two ollas at once, instead of just one, increasing the efficiency of cooking and wood use. Lastly, with a chimney in the back, it draws the smoke out of the cooking area and releases it above the roof line, benefiting the health of the cook and her family.

In talking about the estufa lorena with some of the folks on the island, we already have requests for about four or five. If we make just that many, it will be a pretty impressive change, and something we hope the folks here will be able to continue teaching and building with each other.

One of the main kitchens we hope to change is in the school. Everyday, two moms of kids in the school come in and cook a cream-of-wheat type vitamin drink for mid-morning snack, and then a lunch of rice and beans. The school kitchen is a one room building with black roof and walls due to the smoke, and often the cooks have to step outside to avoid the smoke. If the Madres and Padres de Familia (the equivalent of the PTA) are interested, we hope to build a large estufa there, which not only will make a huge difference to the cooks each day, but will also provide a great place to demonstrate the estufa to a wide audience of island cooks.

In talking about the estufa lorena with some of the folks on the island, we already have requests for about four or five. If we make just that many, it will be a pretty impressive change, and something we hope the folks here will be able to continue teaching and building with each other.

One of the main kitchens we hope to change is in the school. Everyday, two moms of kids in the school come in and cook a cream-of-wheat type vitamin drink for mid-morning snack, and then a lunch of rice and beans. The school kitchen is a one room building with black roof and walls due to the smoke, and often the cooks have to step outside to avoid the smoke. If the Madres and Padres de Familia (the equivalent of the PTA) are interested, we hope to build a large estufa there, which not only will make a huge difference to the cooks each day, but will also provide a great place to demonstrate the estufa to a wide audience of island cooks.

As for us, right now we are planning on a gas stove and probably an estufa as well, so we can boil big pots of water to occasionally wash clothes in hot water, and because it can serve as an oven after warming up - and we´d love more brownies (even without cold milk) and maybe to make a pizza!

Thanks for the question Bill, and everyone, feel free to ask more! We´ll do our best to answer them as soon as we can!

Please believe me that not every moment is spent sitting in a hammock with a great view...but those moments do happen occasionally. :)

Please believe me that not every moment is spent sitting in a hammock with a great view...but those moments do happen occasionally. :)